In order to be able to fire using quick-loading, guns had to be breech-loaded rather than muzzle-loaded.

This had been achieved with the Armstrong gun,

but it had temporarily given way to smoothbore muzzle-loaded guns.

Another innovation needed was 'smokeless powder', that did not obscure the vision of the gunners with smoke.

This was also almost four times as powerful as ordinary gunpowder, allowing for lighter guns with longer barrels.

The most important improvement was the development of buffers to absorb the recoil of the gun when it fired.

This eliminated the need to re-aim it after each shot.

Quick-firing innovations ran parallel with the switch to steel.

From the middle of the 19th century CE, the German industrialist Alfred Krupp had introduced the first guns with steel barrels.

At first these were not superior to the existing bronze and iron guns.

But when the Bessemer process was introduced, cheap yet good quality steel swept the competition aside.

By 1890 CE all gun barrels were made of steel.

The first quick-firing guns were developed during the 1870's CE, though saw no widespread use until after 1880 CE.

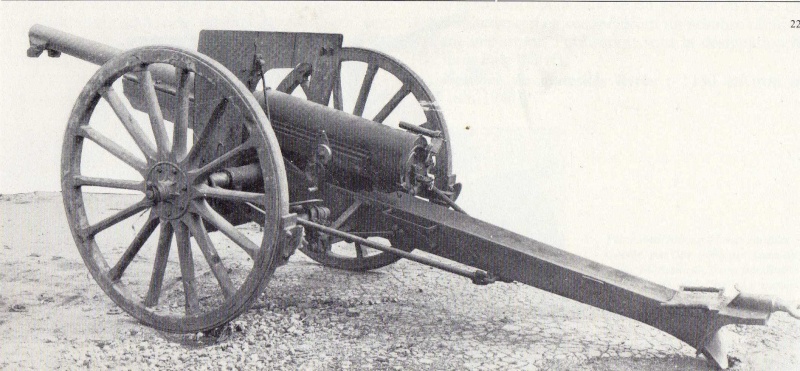

The gun that combined all features and became the 'father of modern artillery' was the French "Canon de 75 modèle 1897", introduced in 1897 CE, as the name says.

It was the first field gun that had a hydro-pneumatic recoil absorption system.

It also used single-piece ammunition, which combined bullet, propellant and fuze into a single cartridge, speeding up the loading process.

On average it fired 15 shots per minute, up to 8.5 kilometers away.

The 'French 75', its upgrades and derivatives saw use well into the 20th century CE, up to World War II.

All the improvements allowed the artillery to fire over many kilometers distance, too far away for gunners to see if they hit or not.

They were forced to resort to 'indirect fire', using marker points and forward observers to make corrections to the alignment of the guns.

Communication equipment, to signal observations back to the artillerists, became important, though was still primitive and unreliable.

Artillerists had to relearn how to shoot and adopted indirect fire with reluctance at first.

This conservatism delayed widespread use of indirect fire until the early 20th century CE.

By then a whole range of aiming, observation and communication methods developed:

telephone; spotting by aircraft; sound ranging; flash ranging; telescopes & binoculars; scales; maps and firing tables.

War Matrix - Quick-firing gun

Second Industrial Revolution 1880 CE - 1914 CE, Weapons and technology